The Jury is In–Chemical Sunscreens Are Guilty of Harming the Reefs.

It was just two years ago when scientists began increased discussions about the possibility of chemical sunscreens harming reef environments. Always at the forefront of reef preservation, the island of Bonaire, coordinated by STINAPA and funded by the island and national governments and WWF, commissioned research to further investigate this potential threat to reefs.

Dr. Diana Slijkerman of the Wageningen Marine Research Unit, in the European Netherlands, presented her findings at a recent Connecting People with Nature presentation by STINAPA. The use of chemical sunscreens is just one more threat to reef habitats around the world.

Reefs around the world are already stressed. They are dealing with many different threats, including:

- coastal development,

- warming seawater temperatures,

- stormwater runoff,

- deforestation,

- oil and chemical spills,

- and agriculture, just to name a few.

Now humans are adding chemical sunscreens to the world’s already burdened reefs.

There are two main types of sunscreen.

Chemical Sunscreens.

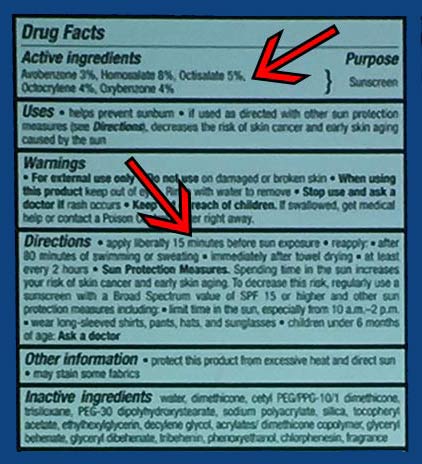

The popular ones used today are chemical-based. They might have, as their active ingredient, one (or possibly a combination) of these chemicals:

Note these chemicals may be found under other names as well.

These chemicals do not block the sun’s rays like physical sunscreens, but instead, they allow the skin to absorb the UV rays, transforming them into non-damaging wavelengths of light or heat.

Physical Sunscreens.

Physical sunscreens prevent UV rays from hitting the skin at all, by creating a reflective barrier using naturally occurring minerals. (Remember the days when lifeguards smeared white-colored zinc oxide over their noses?) These reflective barriers simply bounce UV rays away, so no sunlight is penetrating into the skin:

Different strokes for different folks–various regions use different chemicals in their sunscreens.

Dr. Slijkerman’s research uncovered an unusual fact. By sampling water in Lac Bay–which is somewhat contained by the barrier reef and not constantly getting refreshed by ocean currents as occurs on the coastlines or at Klein Bonaire–she tested for the presence of chemical sunscreens. Surprisingly, she could determine the origin of the people using Lac Bay at the time of sampling, simply by identifying which chemical was prevalent in the water.

Chemical sunscreens manufactured in the EU often use octocrylene for the active ingredient. Chemical sunscreens manufactured in the United States generally tend to use oxybenzone as the most popular active ingredient. Since oxybenzone was also the one chemical originally cited as having potentially deleterious effects on the reef, this is the chemical upon which high focus was given during the research.

Oxybenzone, the good, the bad, and the ugly.

Actually, there is nothing good about oxybenzone.

Oxybenzone acts as an endocrine disrupter.

Oxybenzone acts as an endocrine disrupter.

Relative to reef environments, oxybenzone harms or kills coral larvae by inducing deformities.

Remember that with chemical sunscreens your skin absorbs all the ingredients as well–just imagine what the endocrine disrupters do to your body!

With many chemical sunscreens, the chemicals stay intact and are eliminated from your body via fluid waste after passing through major organs. That means, even if you are just sitting on the beach, the chemicals from your sunscreen are still added to the environment via wastewater. Or, simply taking a shower at the end of the day washes additional contaminants into the ecosystem. Entering the ocean slathered with chemical sunscreens is causing real environmental damage.

Oxybenzone induces DNA damage and viral infections of corals.

Viruses live on coral reefs, just like they do in any terrestrial environment. The recent research has indicated that viral infections of corals are on the rise, and a correlation has been established between oxybenzone and increased infections.

Oxybenzone bio-accumulates in the tissues.

Oxybenzone may increase coral bleaching.

A 2008 study indicated that coral bleaching was exacerbated by viral infections (Danovero, Robert, et al. “Sunscreens Cause Coral Bleaching by Promoting Viral Infections.” Environmental Health Perspectives 116.4 (2008) 441-447.)

A further study in 2016 indicated that the endocrine disrupters affected corals (as well as fish, mammals, algae, crustaceans, and humans) with

(Downs, C.A., Kramarsky-Winter, E., Segal, R. et al. Arch Environ Contam Toxicol (2016) 70. 265.)

How much is too much?

What if my sunscreen doesn’t list oxybenzone?

It is possible that the ingredients in your sunscreen use different chemicals, or they might use a different name for oxybenzone.

Furthermore, just because your particular sunscreen uses another chemical to provide sun protection, it still can be causing harm. There simply is not enough data yet on all the various chemicals used by sunscreen manufacturers to be sure.

How can I check if my sunscreen is chemical-based?

The best way is to read the active ingredients on the label. If you see titanium or zinc oxides as the active ingredients, you are good to go!

The best way is to read the active ingredients on the label. If you see titanium or zinc oxides as the active ingredients, you are good to go!

If you see anything else, it’s best to search for another alternative.

A very simple test (although not foolproof) is to read the instructions for use: If your sunscreen says to apply it 15 to 20 minutes before sun exposure, then chances are it is a chemical-based sunscreen, and it’s best to find a natural alternative utilizing zinc and titanium oxides as physical barriers.

What can I do for sun protection while visiting Bonaire?

There are a number of methods visitors can employ to reduce the effects of hazardous chemicals in the ocean, while still having proper sun protection.

Choose your sun protection wisely.

Be aware of false marketing claims and read the ingredients.

Many sunscreen manufacturers these days use marketing ploys to make you think their products are environmentally friendly. Use of the phrases “all natural” or “safe for the reef” might be true. And then again, they might not. Read the labels.

If engaging in any watersport, wear sun protective clothing.

If swimming, diving, or snorkeling, wear a full-body skin or wetsuit, such as the ones sold at Carib Inn. A thin, lycra hood will also avoid sunburn to the neck. Utilizing such items will drastically reduce the amount of sunscreen needed and you’ll enjoy excellent sun protection, without worrying about sunburns ruining your vacation.

If you’re lounging on the beach, remember it’s not healthy anymore to have that nice tanned look, so check out SPF clothing. If you are not yet familiar with SPF or UPF clothing, there is a great guide to finding the right sun protection clothing.

Wear a hat.

Wearing a hat significantly reduces the amount of sun that can reach your face. Floppy, broad-rimmed beach hats are always in vogue for the ladies, while what guy wouldn’t want to wear a tropic-weight version of a Crocodile Dundee hat, complete with optional neck protection?

Help Bonaire keep our reefs the healthiest in the Caribbean.

So, if you only take away a few thoughts from this information, let them be these:

(Source: Bonaire Insider Reporter)