Dr. Ruth Winters (biologist) and Mr. Michel Pirotton (oceanographer) explore the use of blue light during underwater fluorescence photography on Bonaire.

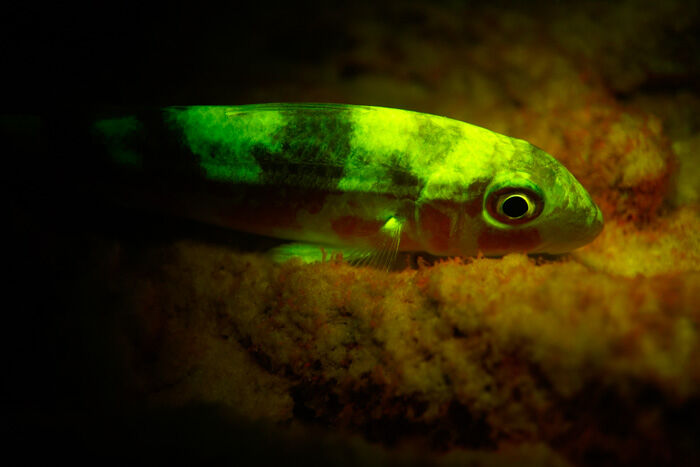

In February, I introduced Bonaire Insider readers to the use of fluorescence photography for plant life here on Bonaire, but I promised a fascinating follow-up as to how Dr. Ruth Winters and Mr. Michel Pirotton use this process in photographing Bonaire’s underwater marine life, both corals and other invertebrates, and yes, even fish, which can all use fluorescence to expand their underwater color range. Think of the scorpionfish, which can show its presence easily to other scorpionfish nearby by using fluorescence, without having to advertise its presence to potential predators, which cannot “see” the red light produced by the fluorescing scorpionfish!

All these animals fluoresce, so, sit back and prepare to be amazed, as we explore the use of blue light in underwater fluorescence photography.

Why use blue light in underwater fluorescence photography?

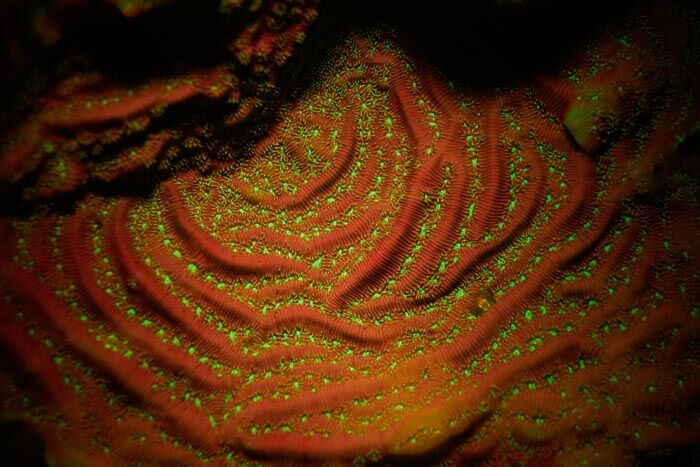

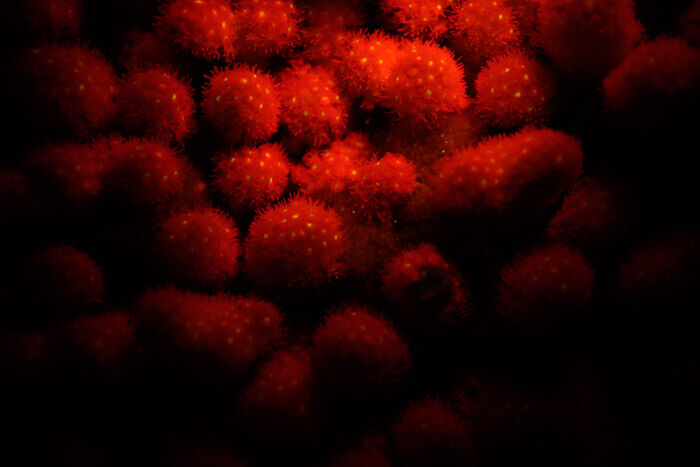

Corals are known to fluoresce when exposed to short wavelengths, and they do this most spectacularly under the blue light of 450 to 465 nm by turning the emitted blue light into neon-colored shades of lime green, orange, or red. But to observe only the pure fluorescence, you need an appropriate yellow barrier filter to remove the emitted blue light.

This fluorescence is generated by special proteins in the polyps and their surrounding tissue showing us the different coral sections in various colors.

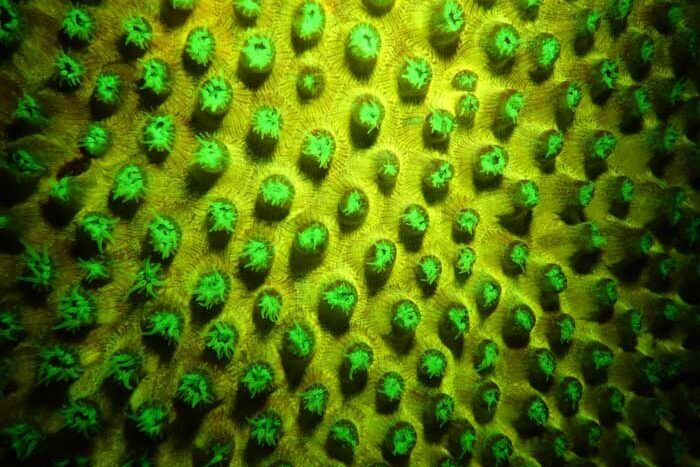

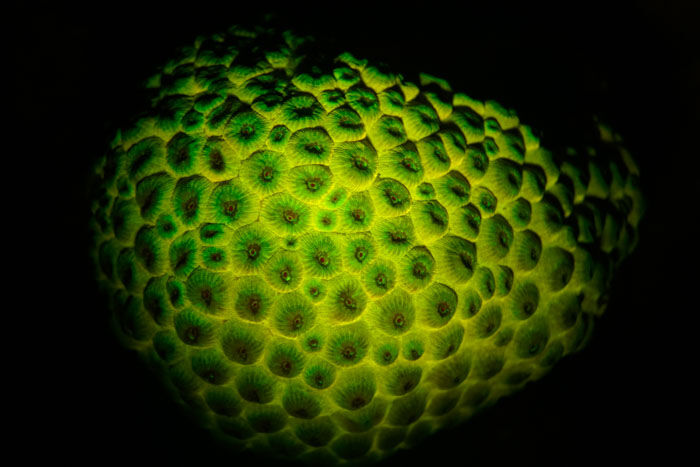

But that’s not all–even neighboring colonies of the same species can turn the blue light into different color patterns, as you can see in the images of the Great Star Corals below. So, the color of fluorescence is not a species-specific feature!

As you may know, corals live in symbiosis with micro-algae, called zooxanthellae. These provide the corals with photosynthesis products like sugar and, in return, receive a nice home from the coral polyp. In shallow water, the fluorescence of the corals is known to protect against ultra-violet light. In deeper water, the corals use fluorescence to generate a suitable light for the photosynthesis of their symbiotic zooxanthellae.

For us, the fluorescence of corals can be used as an indicator of their vitality!

What equipment do I need to do Bonaire underwater fluorescence photography?

You’ll need to provide blue light underwater to stimulate the fluorescence.

A special underwater light for your night diving activities will be necessary to provide light in the optimal color spectrum, 450 to 465 nm.

Additionally, you’ll need an appropriate yellow filter for your camera as well as in front of your own eyes to get pure fluorescence results. Because human vision and our camera’s “vision” will not be able to properly see the fluorescence, we must filter out some of the blue light.

To do this, Ruth and Michel utilize a special over-the-mask shield to wear on their night dives as illustrated here. The camera system in use must also be fitted with a yellow filter (e.g. Tiffen Yellow #12) in order to take spectacular fluorescence images.

But be very careful doing underwater fluorescence photography! You will see nothing else than fluorescence. That means that it’s like diving in the dark. You can’t see barriers or anything in your path, or the ocean floor’s substrate. So, move very slowly so as to not bump into corals and other animals, which is definitely not a good thing!

Gallery of Bonaire underwater fluorescence photography.

Click on any image to view it in a larger format.

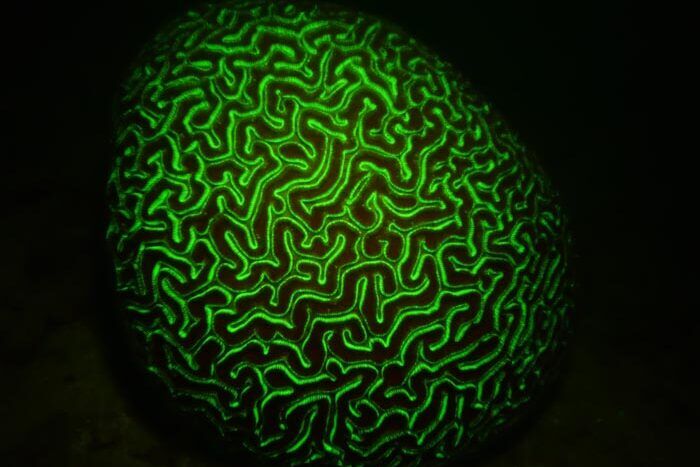

Grooved Brain Coral

Great Star Coral

Whitestar Sheet Coral

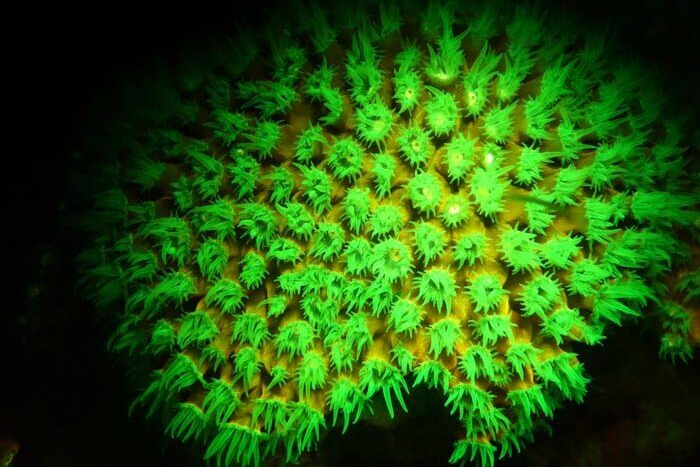

Lettuce Coral

Finger Coral

Blushing Star Coral

Mustard Hill Coral

Lobed Star Coral

Giant Anemone

Spotted Scorpionfish

Sculptured Slipper Lobster

Bearded Fireworm

Spotted Spiny Lobster

Yellow Goatfish

Future uses of Bonaire underwater fluorescence photography.

The use of underwater fluorescence photography opens up new avenues for the protection and preservation of corals and other marine creatures. For example, a dead coral colony will no longer fluoresce, while new coral colonies will fluoresce quite brightly. If a coral colony is sick, or enduring stresses, it is much easier to see the destructive damage of an illness by noticing the loss of fluorescence. Therefore, underwater fluorescence photography might be an important tool in the future for Bonaire’s coral reef monitoring.

About Dr. Ruth Winters and Mr. Michel Pirotton.

This dynamic couple brings together advanced education and training in both biology and oceanography, so they are ideally suited to explore more of Bonaire’s underwater fluorescence photography and possibly assist with future applications for conservation and preservation efforts. We look forward to their next visit in November 2022, when they will be able to capture additional images and provide more data.

To view more of Ruth and Michel’s fluorescence photography, or to learn more about the process, visit their website.

(Source: Dr. Ruth Winters (biologist) and Mr. Michel Pirotton (oceanographer)